Can’t win in Digital (Media) with Divisional Org Structure

Originally published in The Times of India. This article is part 4 of a series called ‘Reality Check on Media Strategy’.

Disney and Marvel have achieved significantly higher valuations than Warner Bros. and DC Comics, largely due to a cohesive strategy that contrasts with Warner Bros.’ fragmented approach. Marvel is valued at $20-$30 billion, Disney at $160-$200 billion, while Warner Bros. Discovery, DC Comics’ parent, is valued at $40-$50 billion. This valuation gap underscores the importance of strategic alignment.

Distribution Dissonance

In 2012, Disney’s deal with Netflix granted the streaming giant exclusive U.S. rights to Disney’s content starting in 2016. However, this arrangement diluted Disney’s brand by associating it with diverse and often conflicting content on Netflix’s platform.

By 2019, Disney rectified this by launching Disney+, consolidating its brands like Disney, Marvel, Lucasfilm, and Pixar into a single platform. This centralized Disney’s relationship with fans, increased brand loyalty, and positioned Disney as a direct competitor to Netflix. Disney+ offers a curated brand experience aligned with Disney’s values, enhancing its brand integrity and market position.

In contrast, DC Comics, until 2020, prioritized individual superheroes’ profitability within its TV studios, selling each superhero’s content to the highest bidder. This led to a fragmented cinematic universe scattered across various networks like CBS, Fox, NBC, AMC, Syfy, WGN, and CW, diluting the brand’s strength.

Narrative Coherence

Marvel shifted from maximizing individual superhero profits to enhancing overall business value through interconnected content programming. This approach, spanning films, TV shows, and animations, has deepened fan engagement with the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU). Characters like Phil Coulson, Iron Man, Captain America, and Thor have consistently appeared across multiple mediums, creating a seamless narrative that keeps audiences invested.

Conversely, DC Comics’ fragmented distribution strategy resulted in disjointed content programming. For example, the Flash was portrayed by different actors in the TV series and the Justice League movie, leading to inconsistency and potentially weakening brand cohesion.

Divisional Organizational Structure

One contributing factor to DC Comics’ challenges, much like those of many media companies, is the use of a divisional organizational structure. Large offline businesses often rely on human effort and are split into separate divisions, each led by a leader accountable for its own profit and loss, operating independently using business rules.

This organizational structure works when each division serves a unique target audience with no overlap in sales channels, like Amazon Web Services and Amazon.com. However, it becomes a performance damper when multiple divisions, each with their own revenue model, target the same audience on the same platform.

Here’s how it impacts the business:

DC Comics & Local Optimization

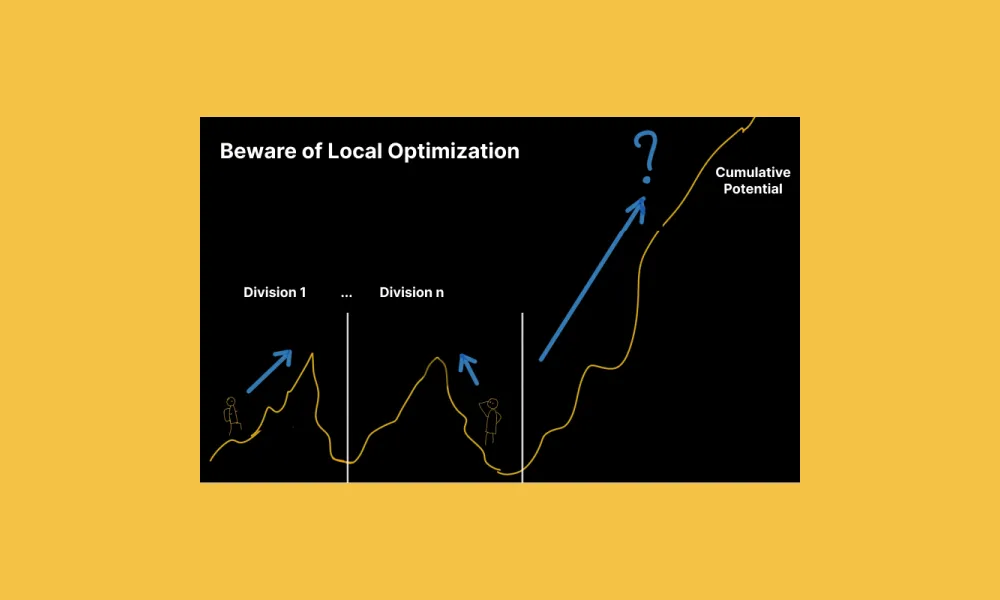

With each division leader making seemingly small, independent decisions within their own silos, the cumulative effect over time can lead to a revenue outcome that isn’t representative of the organization’s cumulative potential — an unintended consequence that no single divisional leader would have foreseen or wanted.

This happens because one division’s funnel optimization can negatively impact another division’s funnel. Additionally, this lack of coordination complicates cross-selling and increases customer acquisition costs for all divisions.

Vox Media & ‘House of Brands’

In the absence of ad-targeting software, media companies can only sell somewhat targeted advertisements by adopting a ‘house of brands’ strategy — having a brand for each target audience.

This approach fragments audience loyalty. For instance, a reader might use Vox for news but turn to Wirecutter (part of The New York Times) for product recommendations instead of The Strategist (part of Vox).

This problem worsens when each brand starts venturing outside its niche to dominate search and social results. For example, a lifestyle site covering hard news.

As the media company’s value proposition fragments, overall brand strength dilutes, eventually resulting in low direct traffic, organic app installs, login rates, and subscription potential. Most of this traffic migrates to algorithmic marketplaces like Google, Amazon, and Netflix, each scaling globally to meet all user needs.

Digital Transformation

There’s a great X thread by Alex Watson, the ex Head of Product at BBC, where he says:

“Low margin businesses (e.g. many media biz) often create an internal culture of ‘survival of the fittest’, where different divisions compete, viciously, to eke out another 0.5% profit. Makes digital transformation even harder…”

Divisional structures breed dysfunction when collaboration is key. Execution slows as divisions grow, each with its own way of doing things, leading to complexity.

- Digital businesses with divisional structures often end up bundling, unbundling, and re-bundling teams and tech for minimal efficiency gains.

- Division leaders fight for resources, creating a zero-sum game where influence trumps merit.

- Gatekeepers, delays, inefficiencies, and bureaucracy expand, blurring roles and diminishing accountability, sidelining company goals for personal interests.

Yahoo! & Peanut Butter Strategy

In 2017, the once-mighty Yahoo! sold to Verizon for a mere $4.48 billion. Almost a decade earlier, in 2006, when Yahoo!’s valuation was almost 10x higher, Brad Garlinghouse, a Sr. VP, wrote a now-famous memo called the ‘Peanut Butter Strategy.’ While you should read the entire memo, here are a few lines that stood out:

- “Our current course and speed simply will not get us there. Short-term band-aids will not get us there.”

- “We lack a focused, cohesive vision for our company. We want to do everything and be everything — to everyone.”

- “We are separated into silos that far too frequently don’t talk to each other. And when we do talk, it isn’t to collaborate on a clearly focused strategy, but rather to argue and fight about ownership, strategies and tactics.”

- “I’ve heard our strategy described as spreading peanut butter across the myriad opportunities that continue to evolve in the online world. The result: a thin layer of investment spread across everything we do and thus we focus on nothing in particular.”

- “For far too many employees, there is another person with dramatically similar and overlapping responsibilities. This slows us down and burdens the company with unnecessary costs.”

- “This forces decisions to be pushed up — rather than down. It forces decisions by committee or consensus and discourages the innovators from breaking the mold… thinking outside the box.”

- “We end up with competing (or redundant) initiatives and synergistic opportunities living in the different silos of our company. For example, YMG video vs. Search video.”

- “We have awesome assets. Nearly every media and communications company is painfully jealous of our position. We have the largest audience, they are highly engaged and our brand is synonymous with the Internet.”

- “We can’t simply ask each BU to figure out what they should stop doing. The result will continue to be a non-cohesive strategy. We need to place our bets and not second guess.”

- “The current business unit structure must go away. We must dramatically decentralize and eliminate as much of the matrix as possible.”

Here’s what happens:

Division leaders tend to be general managers instead of functional experts. General managers, often lacking the ability to identify breakthrough technical opportunities, resort to design by committee. This process prioritizes internal consensus and harmony over finding the optimal solution.

As decisions get pushed up, leaders receive conflicting information from division leads, gatekeepers, and experts, making prioritization tough. This results in spreading investments thinly across multiple bets, with no bet getting enough investment to mature into a revenue-generating asset or strategic differentiator.

Meet In The Middle

Big transitions force trade-offs between divisions. Lacking insight, general managers misinterpret conflicts as interpersonal issues and resort to negotiation — getting division leads to a zone of possible agreement instead of addressing critical issues, which worsen over time.

If a flight from Los Angeles to New York is off course by 1 degree, it will end up 40 miles away from the New York airport. This small error at the start adds an additional 1–1.5 hours of travel time (the time it takes to drive 40 miles in New York), increasing the total travel time by 20% to 25%.

AirBnb & Lack of Focus

Beyond general managers are the functional technical experts — Engineers, Designers, Testers, Editors, Producers, etc.

The lack of clarity at the top trickles down, making functional experts more like the chicken than the pig in ‘Scrum’s chicken and pig metaphor.’ When making breakfast (ham and eggs), the chickens are involved because they provide “eggs” without significant sacrifice, while the pig is fully committed because they are the breakfast.

This happens because, instead of five functional teams working on one impactful strategy, each team works on five different strategies. Brian Chesky, the founder of Airbnb, highlighted a similar problem in a recent interview.

Conclusion

Eventually, there is information breakdown. Despite the budget and resources poured in, no one really knows why the outcome isn’t really moving. Somewhere between the janitor and the CEO, reasons stop mattering. To address these, media companies should consider restructuring to adopt functional or matrix organization structures.

This article is part 4 of a series called ‘Reality Check on Media Strategy’.

—

Want to republish it? This post was released under CC BY-ND — you can republish it as is with the following credit and backlinks: ‘Originally published by Ritvvij Parrikh on The Times of India. The author retains the copyright and any other ancillary rights to the post.