To understand NFTs, learn to recognize collectibles

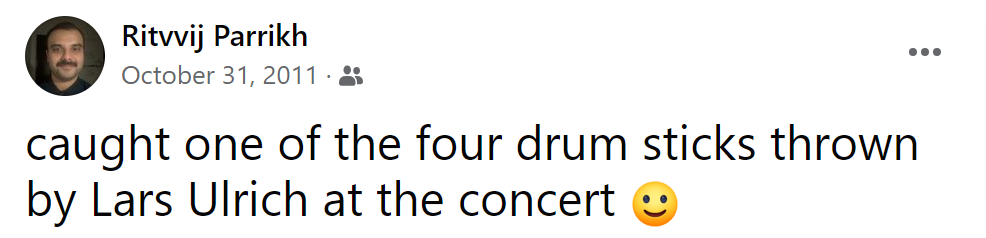

In 2011, a few friends and I drove from Mumbai to Bangalore to attend Metallica’s concert that 29,000 people attended. Lars Ulrich, the band’s drummer, threw four drumsticks into the crowd. I caught one.

It’s 2021. I still have the drumstick but no way to prove that Lars used it except this Facebook post from that period.

And even if this Facebook post becomes proof of some sort, there’s no way to know the physical object being put for sale right now is actually the one that Lars threw and I caught.

In a gist, this is the problem that NFTs solve.

What is a collectible

Humans have always been interested in owning objects for self-expression and identity. So, people hold seashells, animal hide, peacock feathers, pearls, and gemstones.

When millions of people have a deep emotional connection over objects, these objects become irreplaceable. For example, some Buddhist monasteries hold the cremated remains of the Buddha. This is also what makes Ganga Jal (water from the river Ganga) valuable to Hindus as compared to any other water.

For any object to be collectible, social consensus must emerge among a large enough population that the thing is rare, difficult to fake, and easy to exchange.

Since we are writing for an Indian audience in The Times of India, let us take the example of Shaligrams and Rudraksha beads.

Rare. These objects are relatively rare simply because of how specific the supply source is. Shaligrams are naturally occurring riverbed stones in a particular tributary of a river in Nepal. Rudraksha is the dried fruit of a specific species of trees that grow in high-altitude areas.

Social consensus. But then so would riverbed stones of a particular river, say in Madhya Pradesh, or dried fruit of another tree species. What makes them collectible is the intangible religious value that many Hindus attach to them. For people outside this community, both the Shaligram and Rudraksha have no value.

Trust. Both of these products can likely be faked. Hence, often they are purchased only from people you’d trust.

Easy to exchange. Finally, both are non-perishable and small, making them easy to carry and exchange.

Media as collectibles

But, what about the creative media that humans produce, like songs, stories, paintings, music, and poems?

Performers as collectibles. Before the invention of the printing press and later, LP records and photographs, there was no way to store and exchange this media. So these highly talented creators of such media became the collectibles back then. Hence, history celebrates Emperor Vikramaditya and Emperor Akbar for collecting navratnas in their respective courts.

LPs as collectibles. By the 1970s, cassette tapes became the preferred medium to store audio music and records. Yet by the 1990s, out of print, original LP records remain collectibles, whose price has remained stable over the years. Yes, they are rare, difficult to fake, and easy to exchange, but most importantly, they hold a solid nostalgic value.

The Internet disrupts the Industry. The technology shifts of the 1990s enabled anyone to make identical copies of any media — music, art, movie, article, books — at nearly no additional cost. The increase in supply made media abundant, and hence it stopped being a collectible. What followed was a crackdown on Napster and illegal digital media.

We moved to renting instead of owning. Apple iTunes established a profitable business model on the Internet for music. Instead of selling you songs, iTunes licensed you the songs you live at as low as 99 cents. However, you could not resell this music or share it with a friend for the weekend or even move out of Apple’s walled garden.

Owning mass media won’t be a thing again. They have too strong a daily utilitarian value. Hence, you’ll continue to rent a mass-market Amitabh Bachchan movie from Amazon Prime at extremely low prices.

Owning collectibles is a different thing. Collectibles do not need a utilitarian value. The value of a collectible from Amitabh Bachchan is derived from what is the social consensus among Amitabh Bachchan fans about the rarity of the collectible.

Can this collectible be digital media? Until now, no. If Amitabh Bachchan personally wrote a five-line poem and gave it to you as a TEXT file in a pen drive, then there is no way to prove that this poem came from him or that you did not alter it.

Blockchain can change that

Blockchain is a technology that establishes trust. It does so by doing three things:

- It records information in a way that no one can change.

- Anyone can access this information and verify it.

- It is participatory in nature, i.e., to participate, you have to sign up and believe in the system to participate.

Here’s how it would work. Amitabh Bachchan, the creator, will add an entry into Blockchain that they transferred the rights of the original copy to you, the buyer. So now there is untamperable proof that you bought something directly from Amitabh Bachchan. And then it is out there in the open for anyone to see and verify. Then, when you further sell it, you’ll make another entry in the Blockchain recording the transaction.

That’s an NFT.An NFT is nothing but a media asset with its authenticity logged on Blockchain. NFT stands for Non-Fungible Token, which means this media is irreplaceable and unique. For example, there can be a million fake copies of that poem of Amitabh Bachchan for others to read, but there is only one original that you own.

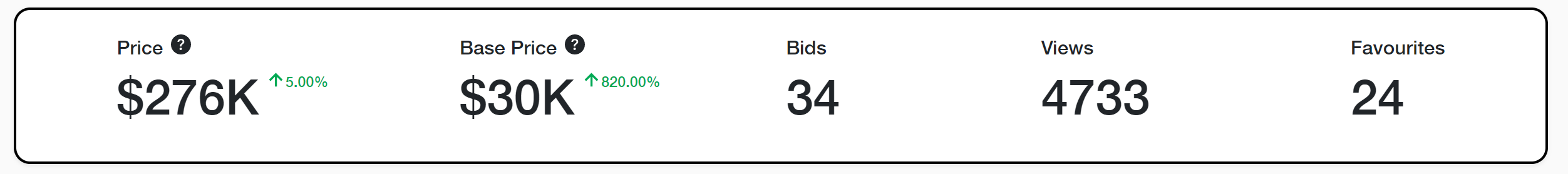

BTW, if you are a fan of Amitabh Bachchan, then do google for — “Amitabh Bachchan NFTs.” He is selling NFTs. One of the NFTs was an audio file of Amitabh Bachchan narrating his father’s poems. He listed the price of the NFT at Rs. ~22 Lakhs. What followed was aggressive bidding between fans, and eventually, this NFT sold to the highest bidder for a whopping Rs. ~3.6 crores.